The online ARCHIVES contain Amos O. Osborn's 1886 History of Sangerfield and also a small excerpt regarding the history of the Hop Industry.

This writing, however, is not not available on-line. I certainly don't think you should stop what you're doing to read it right this minute, but you might want to copy and paste it into a document to save for the Wintertime!

The writer indicates that the year is 1902. Could it be that "C. G. Brainard" was Charles Greene Brainard? If so, the paper must have been written when he was a fairly young man - perhaps in college. He and his wife, Marion, lived on Putnam Street and both were delightful and generous people. They were great friends with Dan and Mary Conger and Hilda and Edward Barton and all were prominent citizens and leaders in the community.

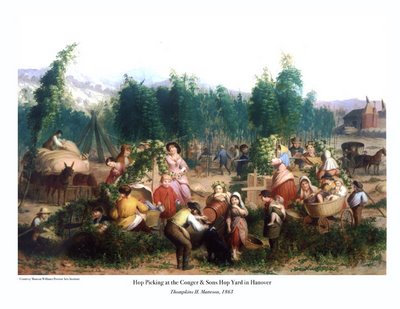

"Hop Picking," by Thompkins Matteson, was painted in the Conger Hop Yards in Hanover and is in the permanent collection of the Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute.

HOP-PICKING IN CENTRAL NEW YORK

By C. G. Brainard

The picturesque season of hop-growing is picking-time. This begins about September first. That district of Oneida county, New York, lying near the village of Waterville furnishes probably the most typical condition. Here in the early history of the industry was the principal market. A record of the fortunes made and lost by the hop-dealers and speculators would make a story by itself.

September is a beautiful month in central New York, but if you have friends living in the hop-growing section, don’t write to say that you would like to visit them then, for you will most likely receive a polite note to the effect that it will be very inconvenient to see you at that time. Everybody goes hop-picking, servant girls and all. “Where are you picking?” is the common salutation. The wagons start out for the home pickers, as they are called (those from the village, who pick in near-by yards and return every night), at five o’clock in the morning. In nearly every home a light is burning, for some one or more members of the family are “picking” and have been up for an hour preparing and eating breakfast. All the pickers are at their boxes before seven o’clock. Few return home for dinner, but at the noon hour scatter among the hop-stacks to eat the lunch they have brought.

During the day the yard is filled with the shouts and cries of the pickers. First from one part of the yard, then another, comes the cry, “Hop-sack! Hop-sack!” - the impatient picker continuing her calls till the “yard-boss” finds her box. Her neighbor helps her hold the sack while the “boss” bends over the end of the box and, with a few well-filled armfuls, empties the contents into the sack. After tying the mouth of the sack tightly, he throws it to one side, to be later carried to the hop-kilns. If the picker happens to be a good-looking young woman she needs to be on the lookout, or, while the “boss” is punching her ticket, she will be taken unawares, caught up by the young men of her acquaintance, and put into the empty box, in spite of all her struggles.

The air of a hop-yard seems to be permeated with vigor, and a day spent among the hops will produce a most ravenous appetite. The quantity of vermin is about the only disagreeable feature of hop-picking. Luckily, none of the insects and worms are poisonous; they are merely annoying. There is one peculiar and rare insect commonly called the “hop-merchant.” Some seasons his scales are tipped with silver trimmings and others with golden. When the silver trimmings predominate, the saying is that prices will be low; when the golden predominate, prices will be high. This is a lucky year, and it bids fair for high prices, for the “hop-merchant” has golden trimmings.

Before the law restricting the import of labor under contract went into effect, some growers brought Indians from Canada into the hop-fields. They made excellent pickers. The work was not hard, and they kept steadily at during the week; then on Sunday gave up the day to lacrosse and other sports. The pickings done now by home pickers, foreign pickers, Italians and tramps, according to how a farmer is situated. If he is near the village he uses home pickers, going after them early every morning and taking them back at night. If his farm is two or three miles or more out from the village, and he has no accommodations for boarding help, he gets Italians. He furnishes them with milk and potatoes, and they do their own cooking. Bunks for them to sleep in are put up in almost any place. A shelter of some sort is all they require. The cow-barn, horse-barn or hop-house, whichever is most available is made use of.

The larger growers have “boarding-houses”, and employ either foreign pickers or tramps, as the case may be. “Foreign pickers,” as their name night imply, are not necessarily foreigners, but the term is used to distinguish them from the home pickers. The foreign pickers are men, women, boys and girls from near-by cities, who take this way to get an outing in the country, and are brought into the hop-districts by the car-load and even train-load. The middle of august sees the first of the tramp nuisance. Tramps generally reach the hop country two weeks or more before picking begins. As a rule, they have no money and subsist by begging from house to house in small groups, or gangs of twenty to forty encamp near convenient corn and potato fields.

In Germany, the hops are cured in the sun; in this country they are cured by artificial heat in hop-kilns. The filled sacks are carried by teams from the yard to the kilns. The kilns - one or more in number, according to the size of the farm - are attached to and form part of the hop-house. The hop-house is a store-room for the loose and baled hops. The kilns attached to them are circular or square in shape, according to the notion of the builder. The kiln is in two parts, the furnace-room and the kiln proper above it. The floor of the kiln is made of strong slats laid parallel, about an inch apart. The slats are covered with “kiln cloth,” a sort of jute sacking. The hop-sacks just taken from the yard are dumped on to this flooring about a foot thick on the level. An average-sized kiln will hold eighty boxes or sackfuls. A hot fire is started in the furnace below. The heat dries out the hops in about sixteen hours. Sulphur is placed in pans in the furnace-room and set fire to, which bleaches the hop and helps to yellow it. The steam and fumes sift up through the hops and out through and aperture at the apex of the inverted cone-shaped roof above the kiln. After the drying and sulphuring process, the hops are pushed off the kiln into the shore-house and allowed to cool, in piles. After picking is ended, a rainy day is selected in which to bale the hops; otherwise they would be so dry and brittle that they would become chaffy when pressed. During wet weather, however, they gather enough moisture to prevent this, so that they can be safely trodden into the press, out of which they come in bales ready for shipment.

A crop of hops is one of the most speculative products a farmer can raise. If he does not want to sell his hay or corn at the prevailing prices, he can feed them to his cattle. Hops he can neither feed to his stock nor eat himself. He must sell them to somebody at some price. Until this year for several years past, there have been such large crops the world over, especially in England and on the Pacific coast, that prices have often ruled below the actual cost of production. Previous to the big crop of 1885 there had been a period of short crops and a using up of available supplies, which forced prices in 1882 to the highest on record, - a dollar and a quarter a pound, - the “dollar year,” as it is called. That year the farmers found themselves suddenly rich.

A story is told of one woman, who kept hanging on to her hops and always wanting a cent or two a pound above the market. She figured that if she sold for fifty cents a pound, the proceeds from her crop would be just enough to pay off the mortgage on her farm. She wanted to repair and paint her buildings and five cents a pound more would allow her to do it, but when the market advanced to fifty-five cents, there was something else she wanted and decided not to sell for less than sixty cents a pound. At each advance her wants increased. She was finally offered one dollar and twenty-five cents a pound, which would have netted her on the eighty bales she had raised about twenty thousand dollars. The market had advanced so rapidly and steadily that even this price would not satisfy her. It is hard to imagine the excitement that prevailed. “Two dollars a pound,” was the cry. “Give us two dollars a pound and we’ll all sell, but not for less.” Many and many a farmer argued this way. This misguided woman was one of them. At one dollar and twenty-five cents the market took a sudden turn. Prices crumbled away and she finally sold at eighteen cents a pound.

There is, however, a legitimate side to hop-raising; and if the farmer will sell his crop when it is ready for market, rather than hold on to if for a possible better price, he can make his hops yield him very much more per acre than any other crop he can raise. The following balance-sheet is made up from the books of a successful hop-raiser and shows what profit can reasonably be expected from operating a hop farm.

Expense, Including Six Per Cent

Interest on Investment Receipts

From April 1, 1890, to 159 bales hops...........$11,469.75

April 1, 1891 ........$13, 448.12 Sundry items, including

Gain for year....... 354.37 dairy...............$ 2,332.74

................. ..................

$ 13,802.49 $ 13,802.49

From April 1, 1891, to 273 bales hops............$11,898.86

April, 1, 1892.........$12,417.00 Sundry items, including

Gain for year.......................$ 1613.18 dairy................$ 2.131.32

........................ ...................

$14,030.18 $14,030.18

From April 1, 1892, to 351 bales of hops $ 14,654.05

April, 1 1893 $ 14,089.71 Sundry items, including

Gain for year $ 3.326.90 dairy $ 2,762.56

........................... .......................

$17,416.61 $ 17,416.61

From April 1, 1893, to 358 bales of hops $ 16,631.05

April 1, 1894 $ 14,608.91 Sundry items, including

Gain for year $ 4,280.17 dairy $ 2.258.03

.......................... .......................

$ 18,889.08 $ 18,889.08

Total Net Gain for Four Years

1890 - 1891........................................................................$ 354.17

1891 - 1892...................................................................... $ 1,613.18

1892 - 1893........................................................................$ 3,326.90

1893 - 1894........................................................................$ 4,280.17

.........................

$ 9,574.62

In studying these figures, it should be kept in mind that the gentleman operating these farms had plenty of capital. this enabled him to fertilize and care for his crops during the one or two years of low prices, so that when a high-priced year came around, his land being constantly kept up to the highest point of cultivation, he was sure of a good yield. There is, of course, one danger a hop-grower has to face, - that of a total failure caused by blight and mold, but this calamity is so remote that it need be scarcely thought of. Everything considered, the figures presented above are very fair. They cover a range of four years, and none with prices above twenty-three cents, which is not very high. In fact, the present crop harvested in the fall of 1902 sold as high as thirty-five cents; therefore, considering all these facts, hop-growing as shown by the earnings of this gentleman is proved a highly remunerative branch of farming.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

"Hop Picking" 1902 by C.G. Brainard

Posted by

PsBrown

at

9:35 AM

![]()

![]()